Private James Boswell by Montagu Slater

1929, year of the Wall Street crash, marks in many ways the beginning of this chapter of wars. I remember that it was this year I met a youth with a round boyish face walking through the Regent’s Park Road with a large wooden rocking chair which he planted in mid-pavement when we paused to chat.

The rocking chair, symbol of the Southern States, would have been quite a good totem for Boswell. He used about this time to affect a large unrolled umbrella and a shepherd’s plaid scarf, but I daresay he left the brolly at home when he went to fetch the armchair.

As an art student James Boswell was scrupulously traditional, yet there were one or two traits in which he was untypical. One was speech. He had superimposed on his native New Zealand a faintly American burr and made the understatements of American slang his own. After all, as he will tell you, the States have been a rather more important influence on Australasia than the Mother Country these many years. The other trait in which he was untypical is less definable.

It is more a matter of general attitude - of being a colonial and proud of it, something quite unusual in a colonial art student. It went very well with his habit of singing hill-billies to a guitar, and he later added some not too respectable English folk tunes and old music hall songs. One of the most touching I’ve never heard sung by anybody but Boswell. Does anybody else know it?

“And I’ll water his geraniums. Till my true love comes home.”

I jump forward from there to 1931-32, his student days over. I remember sitting in a lonely house on top of the Chilterns playing chess for days on end with all-too-human chessmen drawn - by Boswell - on cardboard, making fantastic prophecies, many since fulfilled, about the progress of world crisis, and talking about the fall of the Roman Empire and how Roman art and literature were freshened by the colonials like Martial in the last phase. It was a delayed spring. On top of the Chilterns visibility was nil. The fog was all round us. Boswell took to drawing graveyards. It was his favourite subject for three months.

We came down - to Kentish Town. The next ten years were the hardest. We were busy in the back streets of Kentish Town getting to know people.

We learned a good deal. I think. At least Boz did. You can see what he learned in Kentish Town in most of the drawings and lithographs he did in the next ten years. Many have felt about the general run of work in this ten years that it was still “from the outside looking in.” We were making life-long friendships in Kentish Town. There was no nonsense about that. But there’s still a last Chinese Wall for the artist to climb. Different people clamber over in different ways and places. Boz has left the Chinese Wall right out of sight after a year in the Army.

for the artist to climb. Different people clamber over in different ways and places. Boz has left the Chinese Wall right out of sight after a year in the Army.

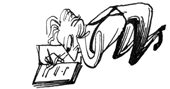

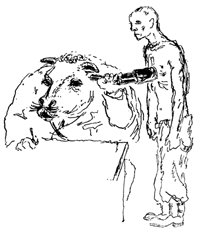

The drawings here are from three fat notebooks crammed with mere God’s plenty. Unfortunately there is a limit to the number that can be reproduced here, though for my part I should like to print all three notebooks en bloc. Those we have printed introduce an issue of Our Time which is largely made up of contributions from the Army. They give us a picture not only of their subjects but of the Good Soldier Boswell.

Montagu Slater (1902-1956) Poet, Novelist, Literary Critic, Scriptwriter and Librettist.

Reprinted from Our Time, March 1942, pp 11-15.