The final years by Ruth Boswell

When I first met Jim in 1962 he was painting dark, sombre abstracts. The Drian Gallery exhibited them in a one-man show in 1962. They were also shown at the Artists' International Association, the Commonwealth Biennale of Abstract Art and other shows. They are powerful, introspective paintings which recall the rugged coast of his native New Zealand and reflect his then state of mind

As I was to discover, the man was as powerful as his work, not in an overbearing way but in the wonderful life force which touched everyone and everything. Being with him was not only stimulating but fun. He was attractive, funny, original and with an astonishing fund of knowledge. I immediately took to him at our first dinner at Bianchi’s Restaurant, (the first of many, that and Bertorelli’s were to become our favourite haunts), especially as he turned out to be not only a descendant of the eighteenth century writer James Boswell with whom I had been fascinated for many years and whose entire oeuvre I owned, but the one time art editor of the magazine that enlightened my schooldays, Lilliput.

I had come to work part time for him as an assistant as he was editing the Sainsbury House Journal, the journal of the Society of Industrial Artists and in 1964, running the publicity campaign and designing the posters that brought the Labour party to power.

Stronger colours were now appearing in his work. An exhibition in Heals’ Art Gallery in 1964 was of abstracts in coloured inks, reds, yellows, purples. They reflected our wanderings around the town and led to a 'Science Fiction' approach to capture London in terms of movement, things seen in reflections in shop windows, through cars, images broken up by constant movement. An exhibition of these drawings and paintings were at the New Vision Gallery in 1966. It was not very successful but I find them intricate and absorbing. The drawings are especially fine.

In 1966 I divorced my husband and Jim left his wife Betty. My three children were in their early teens. We all moved in together into a large, Edwardian house he bought in Muswell Hill. We had already begun going on memorable visits to Venice and in the school holidays took the family, his daughter Sal and her husband Brian Shuel, his grandchildren and my three, to Yarmouth, Isle of Wight and to Margaret Taylor’s beautiful converted mill. Jim loved the long, flat stretches of water of the Venetian lagoon and the Yarmouth estuary which ebbed and flowed outside the mill. I clearly remember how he first tried to draw them by horizontal lines and then, in Venice, in a Eureka moment, realised that the horizontals were made up of uprights formed by thick, wooden painters, reeds and grasses. From then on he drew and painted the estuary landscapes in terms of horizontal bands made up of delicate, upright strokes.

He also, during this period, worked his way to the mandala shape he was striving for, ‘not a pure circle but a living shape like a cell’. It appeared now in practically all his work, sometimes as a mandala, frequently as the sun. It is also the linking theme on a set of record covers he designed for Topic Records.

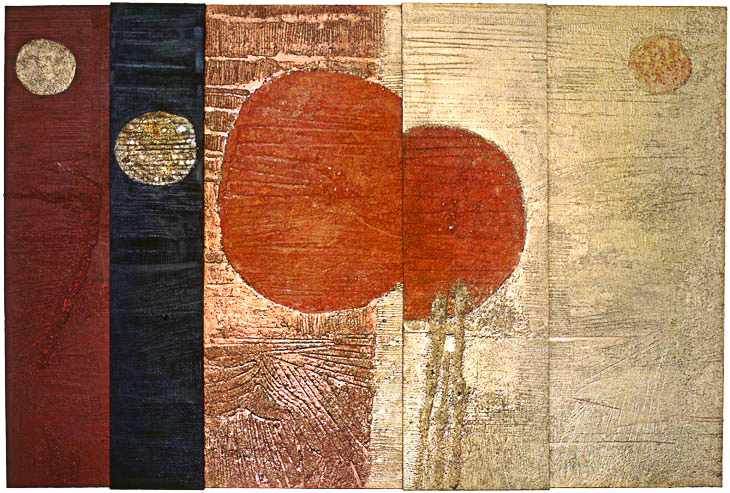

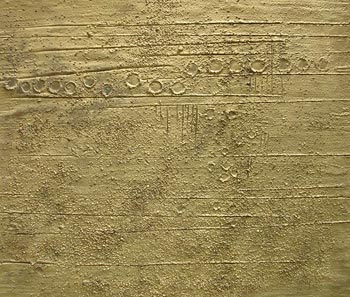

In 1967 Donald Bowen invited Jim to have an exhibition at the Commonwealth Institute in Kensington. We hired a studio from a friend in Belsize Park Road and he worked like mad. Now, instead of mixing sand with oil he made a more solid base with sand, powder paint, polyfiller and a liquid glue. He then laid the canvas flat and indented the mixture. Once this had hardened, he either painted over it with oils, or sprayed it with a wide variety of gold, silver and copper powders, or a combination of both. The exhibition was very succesful with a set of remarkable Shoreham pictures, which I consider to be among his best work.

He had, shortly after we moved in together in 1967, been diagnosed with cancer which was treated. We considered it a cure but it was, as it turned out, only a remission. In 1970 it recurred, though neither of us, even then, looked on his illness with despair. Jim was always hopeful about a cure and I was so determined that he was going to get better that it seemed impossible that it could be otherwise. We went to the top specialist, Dr Hamilton Fairley who was later tragically killed by an IRA bomb, and he put him on a chemo-therapy course administered once every six weeks. This meant that Jim was ill from its effects for three weeks and for the other three we could go into the studio and work. The images flowed from him. He had arrived at the form he wanted his work to take, ‘pure gold surfaces with simple marks to create a very tranquil and undisturbed object’. The gold paintings of the last two years are a coming together of deeply felt influences in his life.

In 1970, the year he fell ill again, B.P. commissioned him to paint a large mural for their new building in Wellington, New Zealand. Though he was in constant pain he never complained and worked in his ‘good three weeks’ on the mural. I think we both knew it was going to be his last work but we didn’t openly acknowledge it. It seemed impossible. One of the amazing things about Jim was that even then he never lost the life enhacing quality that was one of his special gifts. It flowed from him right up to the end. I remember, on his last day, Richard Bennett coming round for Jim’s weekly drawing for the letter pages of the ‘Sunday Telegraph’ and Jim, barely able to sit up, producing one of his inimitable funny drawings.

Because of transport problems the mural is in five tall panels which repeat the mandala and estuary themes. Jim called it ‘The Golden Day’. He wrote:

‘This mural has for its theme the passing of a day. From left to right the five divisions show Dusk, Night, Dawn, Noon, Evening. There is a special beauty in this equivocal kind of ‘edge’ where the land is not wholly land nor water but is constantly changing as the planet turns and the tides move.’

‘The Golden Day’ symbolises the passage of time against a curtain of movement, its subject matter the sun and moon, set against flowing tidal waters. It is clearly about his life and is illuminated by its sense of joy, hope and fulfilment.

After the mural was shipped to New Zealand we went for our last visit to Venice. We walked all over the town and visited the islands, particularly Torcello which we both loved. Jim drew constantly. This last set of drawings is extraordinarily evocative and an altogether original approach to drawing Venice.

He died in St Bartholomew’s Hospital on April 15 1971.

Since then his reputation has grown. There are sketch books, drawings and paintings in the Tate, Victoria & Albert Museum, The British Museum and Imperial War Museum.