Painting

When James Boswell arrived in London from New Zealand in 1925, he came to learn how to paint. The Royal College of Art (RCA) failed dismally to teach him what he wanted to know but painter Freddie Porter took him on and pointed him in what James considered was the right direction. Freddie Porter was a New Zealander who had spent time in Paris and his view of painting bore little resemblance to those of the RCA. Boswell remarked that ‘what he had to teach was la belle peinture and how it should be done. It was as different from painting taught in England as a good claret is from coca cola.’ The RCA disapproved and threw him out but he continued to paint regardless, simple and delicate images of anything he fancied which he showed at any gallery which would hang them. The RCA took him back, he won a scholarship to continue there but went on doing his own thing rather than what they required so they threw him out again. He wrote, ‘You can have no idea how provincial and awful London was in the 1920s. Painting was dreary, academic and rubbishy’. He stuck to his guns and produced so many paintings that one night, he and a friend took all their surplus work and deposited paintings on the front door steps of houses in Fitzroy Square, just round the corner from his studio.

In 1932 he stopped painting altogether and took to graphic art. He didn’t paint again until after the war. Life in the army, particularly a year in Iraq, provided raw material in the form of drawings and watercolours. Hot, red, dirty, dusty deserts, rough, wrecked buildings, sagging tents, overused lorries, exhausted soldiers – he drew everything he saw. When he came home, some drawings were transformed into oil paintings, two of which are now in Tate Britain, both oddly surrealist in flavour. As a child, I watched him paint them in his studio. I wanted to know why he painted the sky red and he told me that it was red which was good enough for me.

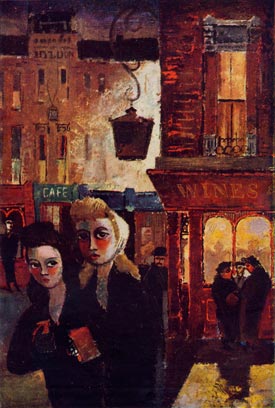

In 1947 he began to paint Camden Town. The paintings were not large and were often more like illustrations than oil paintings. A series of paintings of street scenes appeared in Lilliput, four of which are now buried in the bowels of the V&A and these are wonderful. He wanted to paint but seemed to be uncertain as to how to set about it. He had trouble discovering what it was he wanted to do and occasionally slaved away at a painting for months, often destroying the final version. Well known as an illustrator, he wasn’t recognised as a painter and this was frustrating because he clearly wanted to escape from the social realism for which he was known. In 1952, his circumstances changed and the opportunity to paint and draw – as a student would paint and draw – presented itself. He rented a studio and models and went back to basics.

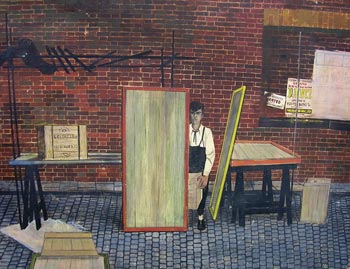

Boswell was often accused of failing to stick to anything long enough to produce a recognisable style. A close study of all his work from the fifties onwards shows that this is not so. He was exploring and as he explored, his style transformed itself seamlessly into whatever came next. The flow of thought was as inevitable as a river running downstream. In a matter of five years he went through many decades of painting techniques. He explored tempera which demanded a delicacy of touch; his paintings were detailed; pebbles, cobbles, timber and brick walls. He took to Fauve and played with bright colour. He explored pointillism, Turner, Monet, Matisse, Braque and Utrillo and as he explored, he learned more about technique. Paint began to obey him. He never took to straight edge painting. He would stand in front of a Bridget Riley or a Mondrian and enjoy it but he didn’t want to go there.

Boswell had an ongoing love affair with the coast from Shoreham to Brighton and produced paintings of the area from the early fifties onwards which reflect every style of painting which he had explored. Some included practically every pebble on the beach, others were simple slabs of primary colour, some were grey and heavy because that was how it was. In the mid fifties he painted a series of green paintings which he called ‘Pastoral’. They were not strictly speaking abstract because they were what you might see if you lay on your back under an early summer tree with the sun shining through. They were different from what he had created previously and were attractive, happy and perhaps a bit lightweight but very easy to live with.

In Autumn 1957, the Tate held an exhibition of American Abstract Expressionism. He was stunned and so transfixed by Jackson Pollock that he embraced abstract painting with heart and soul. He considered the previous five years an impediment but if he hadn’t had five years of learning how to manipulate paint, he might not have been able to cope. He mixed his paint with sand from the beach at Brighton which he washed clear of salt and baked dry in the oven. This he mixed with metallic powders to create bronze and copper; the paintings were powerful and strong. Several were called ‘Tasman’ and were how he remembered the west coast of New Zealand where he grew up. In 1962 he had an exhibition at the Drian Gallery in London and the accumulated work of the previous five years looked magnificent. He had discovered what it was he wanted to do and he knew how to do it.

In 1966, final paintings of Shoreham emerged which summed up completely everything he had been trying to find there for so long. His paintings always reflected his mood. When he was depressed they were sombre. When he was content they were full of light. During the sixties he established a relationship with Ruth Abel. He was content and it showed. He began to explore the use of gold, producing a series of paintings, a golden sun reflected in a golden lagoon – Venice at its most beautiful and where he had been most happy.

In 1970 he was commissioned to do a large painting for the BP Headquarters in Wellington, New Zealand. It’s made as five panels because it’s nearly eight foot high and a good bit longer, is called ‘The Golden Day’ and is just that, Dusk, Night, Dawn, Noon and Evening, cool moon, hot sun and a golden lagoon. It concerns light and dark, love and mystery, life and death and he knew it would be his final work He finished it shortly before he died in 1971.

Sal Shuel