Eyewitness of the Thirties

If humanism were the only requirement in making a work of art, James Boswell would be one of the most important painters and draughtsmen of the first half of the twentieth century.

Born at Westport, New Zealand in 1906, of Scots-Irish parents, he was of a generation deeply affected by the Great Depression and the march of Fascism.

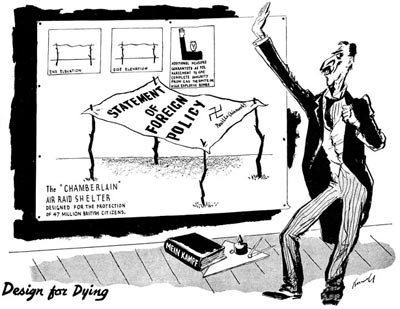

He was a big, much-beloved figure, heroic yet vulnerable, perhaps best remembered for his satirical drawings contributed to Left Review and other periodicals of the Thirties and Forties.

He died in 1971, and this exhibition* is the first to recall him to mind and the first to provide an opportunity to see his early graphic achievement in depth: the caricatures, illustrations, etchings, lithographs and wartime sketchbooks. And since there is now a flow of new studies of the Thirties, the chance to establish Boswell in his proper niche, if welcome, is long overdue.

It is not hard to find reasons for his present obscurity. Politically-motivated social realism has rarely, if at all, found acceptance in Britain. The challenging content of Boswell’s art smacked too much of agit-prop in its time, offending the conventional concept of the role of art. Even though the influential critics of the Thirties (Roger Fry, Graham Bell and Herbert Read) embraced socially radical ideas, they had distinct reservations about anything they thought ‘Low Art’. Much of Boswell’s work therefore, protected by its apparently modest purpose, concealed its high intentions beneath a ‘Low’ disguise by appearing as lithographs in small editions or drawings in smallcirculation periodicals and political ephemera. And yet such work is an essential part of our tradition of political caricature and street literature.

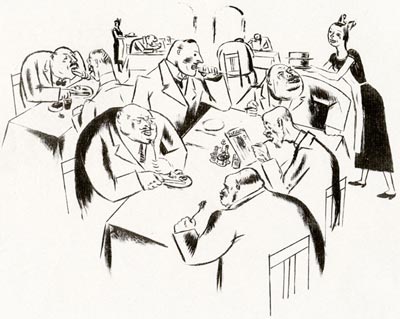

The Great Depression of 1929-1936 made James Boswell the draughtsman of the history of those years and the decade afterwards. He took an active part in much of what he depicted and led the characteristically double life that such an artist invariably leads. By day, he was a successful graphic designer, and later the charismatic art director of Shell’s publicity organisation. But he spent his nights and weekends exploring the streets and pubs of working-class London. Like Daumier and Grosz he had a passion for justice, and the opportunities his executive post gave him to observe City of London types - crooked stockbrokers, lawyers and bankers - enables him with a few strokes to define what he felt could be villainy and double-dealing. Yet he is a satirist, not a caricaturist. Few of his drawings actually deal with a single event or a known person, but they are all dealing with realities.

His friendships with Randall Swingler, Montagu Slater and Edgell Rickword enabled him to play an influential role in reviving social satire as an art in Britain. He was asked to become the unpaid art editor of Left Review (1934-38), contributing drawings himself besides soliciting work from other artists such as his friends, James Fitton and James Holland. Left Review became famous for the drawings contributed by ‘the three Jameses’ as they were called, and its influence on the radical student generation was enormous.

In 1935 I was in my second year at the then Manchester School of Art irritated beyond endurance by the blind self-satisfaction of an unpleasant group of upper middle-class students from socially circumspect suburbia, painfully acquiring the realization that I aspired towards more democratic gods, and finding them in the forbidden pastures of Collet’s Bookshop, Manchester. I remember being spell-bound as I opened several back issues of Left Review to gaze at the trenchant images, ripping apart the social villainy of the Tories while expressing sympathy for the underdog. Then and there, I decided that this was the kind of artist I would be.

Left Review was unique for the Left in Britain even though Francis Meynell and others had collected L ’Assiette au Beurre (1901 -12) - or, ‘the buttered dish’ - that celebrated satirical weekly journal of Belle Epoque France. Founded by Samuel Schwarz, it was unique in that artists were given sixteen pages of a complete number to make uninhibited attacks on bourgeois society. The captions, which greatly enhanced the impact of the illustrations, were written by a group of poets and journalists including Rictus and Richepin. Boswell himself had a collection, acquired on visits to Paris in the Thirties. (In this, see his article ‘The World its Oyster’, Our Time, Vol. 5, No. 11, June 1946, pp 240-41.)

In the pages of Left Review artists collaborated with poets and journalists, and it proved to be professionally-edited, relatively sophisticated magazine journalism of the communist left, comparable to New Masses in the United States and Monde in France. Yet for Boswell it was the beginning of a love-hate involvement. Much of the creative impetus which would have ordinarily gone into his painting now went into a spate of vigorous, often inspired, drawings and illustrations.

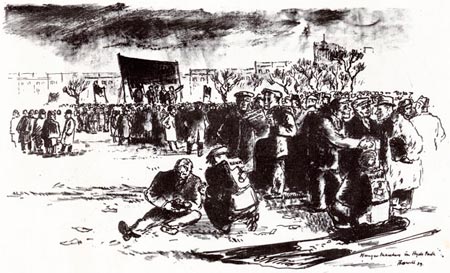

He also became involved with lithography, and from 1933 to 1939 worked with a close friend, James Fitton, to produce a series of mostly black-and-white lithographs from sketchbook studies made on explorations of Camden Town, Kentish Town and the East End. Fitton, a student of A. S. Hartrick at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, had become an instructor of a thrice-weekly evening class in lithography, and he helped Boswell master the medium. Boswell was also kept busy supplying designs for bookjackets and pamphlet covers as well as working as a freelance Special Artist and cartoonist for the Daily Worker, for which he used the pseudonym of 'Buchan'. It was as ‘Buchan’ that he covered the ‘Battle’ of Cable Street of 1936, when 600 foot policemen and many more mounted, attempted to escort a phalanx of Mosley’s uniformed fascists through what was at the time the centre of London’s Jewry and a militant working-class stronghold.

He would occasionally take time off from the political drama in order to draw the social scene, as he did in Paris at the celebrated brothel, the Sphinx: the result of his stay there being a superb series equal to Pascin in revealing the butterfly existence led by its inmates.

Then came the war, and with it a period of Army service which began for him in 1941. He found himself at first in the Royal Army Medical Corps, training as a radiographer. Many aspects of military life disgusted him: the ill-fitting uniforms, the insolence of officers, the calculated system of breaking down the recruit’s spirit and the appalling red tape. All these things filled him with rage and despair and in three sketchbooks he invoked Gillray and Hogarth to satirize Army brass as uniformed bulls making life a senseless nightmare for helpless serving soldiers.

During and after the War he continued the process of reviving the lost English tradition of social satire when he became advisor and oracle to other magazines of the Left. These included the monthly Our Time (1941-52) and the quarterly story magazine, Seven (1940-52). And under his magnetic leadership and influence drawing in England underwent a renaissance. A richly linear idiom, laced with a mixture of Rowlandson, Cruikshank, ‘Dicky’ Doyle and Samuel Palmer, reached its peak in the mass-circulation monthly, Lilliput (1938-52), of which Boswell was art editor from 1947 to 1950. On the editorial side in addition to Richard Bennett, whom he had met in the Left Review days, there were Maurice Richardson, Patrick Campbell and Claud Cockburn. Around Boswell there gathered a group of young illustrators and satirists, among them Arthur Horner, Ronald Searle, Gerard Hoffnung, the painter John Minton, Fritz Wegner and myself. Again, he set the example, contributing intensely-observed, witty and sometimes savage drawings that always delighted because they were so finely and exquisitively drawn.

The sudden collapse of these periodicals removed the economic and ideological outlet for us all. But while most of us struggled on with varying degrees of success to ride what was a temporary setback, Boswell felt it was high time to think of what he himself really wanted to do for the last period of his career. For a little while longer there were flashes of the earlier delight in drawing London life. But on the whole this late work lacks conviction and invention. Even before the demise of Lilliput he had broken with the bureaucrats of King Street. If illustration can be defined as the interpretation of an idea then he no longer believed in the idea. Yet what he had created, redolent as it had been with a commitment to romantic communism, was also alive with comment on, or criticism of, much that was rotten in society making up a history of English life that even today brings to life the idealism, the personal and political problems of the Thirties and Forties.

With typical modesty, he came to consider that this aspect of his art had deteriorated, ‘largely’, as he himself stated, ‘due to a confusion in my own mind as to its purpose.’ The problems involved no longer seemed so black-and-white as they had appeared in his youth. He became much more contemplative, turning back then toward non-objective aestheticism. The wheel had spun full circle. James Boswell had become a painter once again.

Paul Hogarth RA. OBE. (1917-2002) Artist and illustrator.

* Originally published in the catalogue to the retrospective exhibition at Nottingham University Art Gallery, 22 November - 16 December 1976