Remembered

Most people nowadays think of the thirties, if they think of this period at all, as the time of the Great Depression and a depressing time to live through. It was and it wasn’t. The times were depressed but surprisingly, lots of ordinary people were not.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, a grim, poverty stricken, callous time which many poor souls did not survive.

In the face of the incredible complacency of the establishment it was also a time of great gusto, vehemence and vitality, especially if you got into ‘the struggle’. There the prevailing mood was one of irony. Not the classic, detached irony so beloved of literary critics. It was bitter, caustic and deep rooted.

The James Boswell I met in the mid-thirties was a young man of such gusto and vehemence and he was unmistakably in the struggle. In his work and in his conversation he had an ironic sense of humour. He was a thick set fellow with a pleasant, ruddy face, prematurely grey hair and an undefinable accent that hardly hinted as his New Zealand origins. His mouth had a permanent curve to the lips as though perpetually amused at the wonderful and woeful people and incidents of that decade.

He was a frequent visitor to the offices of the Daily Worker off the City Road when, as Gabriel, I joined that paper as cartoonist in the spring of ’39. He had contributed cartoons occasionally to the paper to fill the gap before I joined.

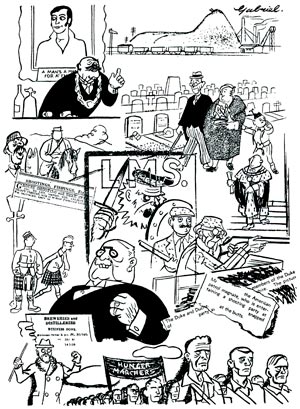

Thirty six was the year Franco started the Spanish Civil War, Mussolini thought he had finished the Abyssinian War and Hitler, by marching into the Rhineland, took his first step toward the Second World War. It was quite a year. At home we had the Means Test, Hunger Marchers, Mosley Rallies, a National Government and the grotesque irrelevancy of the Abdication.

Boswell worked as an artist-designer in one of the big advertising studios. Outside he was a leader of the Artists International Association, a natural organiser and, of course, an artist in his own right. Most of the advertising studios then were hotbeds of subversion and the work done in them was not always what it should be.

I remember Ken Stitt, an ebullient and talented colleague of Boswell’s, telling me the story of one of their executives showing a client round the studio. The cumulative stages of a campaign for the client’s products were roughed out on posters pinned to the wall. At the end, marching the client to the far end of the studio, the executive proudly announced, ‘And the pay-off line is…’ to be confronted by a poster claiming in bold type: ALL OUT MAY DAY.

Artists are not by nature the most organise-able of creatures but they were got to do an enormous amount of work ‘for the cause’ of that period. Party headquarters at King Street and London District headquarters were constantly calling in Boswell and a few selected experts to work out the pictorial side of a campaign, arrange exhibitions, decorate meeting halls or participate in demonstrations. Later, other artists, copywriters, lay-out men and typographers would be co-opted if needed.

Over and above that was the heartening fact that you did not move in a narrow circle of proselytising party members. The popular movement around the anti-fascist struggle, and allied causes, was wider than that.

There was the Left Review, edited by Randall Swingler and Edgell Rickwood, the former an under rated writer and editor, the latter now being re-discovered as a major poet. Between them they brought writers of international reputation to the magazine. There was Unity Theatre having a high old time with political pantomime and American drama, Alan Bush and the Workers’ Musical Association, The Artists International, the Movement for Colonial Freedom, the Unemployed movement, and so on and so on.

Wells, Shaw and Priestley, Augustus John and John Strachey contributed to the pages of the communist Daily Worker. On its staff were scientist J.B.S. Haldane, reporter Claud Cockburn and writer Ralph Fox. Well known Fleet Street journalists gave a hand on their days off. Perhaps most important of all was the Left Book Club whose orange-covered volumes (half a crown a month) influenced the political thinking of a generation. That was the scene.

Incidents rise informally to my mind from that jumble of memories. Boswell’s account, after an early visit to Berlin, of the nauseating sight of Jew-baiter Streicher with a nubile entourage in a public restaurant, Bert (A.L.) Lloyd returning from an Antarctic whaling trip with a series of articles and a magnificent set of photographs, Paul Robeson, dominating the little Unity Theatre in St Pancras, with his performance in ‘Plant The Sun’. And all the time a steady stream of young men volunteering to fight in Spain.

May Day ’36 is the day that sticks in my mind, my first experience of marching. Demonstrations, as I later found out, were normally serious and sometimes downright dangerous affairs, as at Cable Street and Olympia. This was like a gigantic family outing. First view was of a long crocodile of people assembling along the Embankment in the morning sunshine. You looked for your banner and joined your contingent. I joined The Daily Worker contingent and Boswell joined the Artists International. Nearby, the Surrealist Group gathered under their banner and in front of the parade were the London busmen on strike in uniform, headed by their unofficial leaders Bill Jones and Bert Papworth.

As well as trade union branches and party districts there were Co-op Guilds, womens’ groups, peace groups, Unity Theatre and agit prop lorries with actors’ tableaux and set pieces. It took a good couple of hours to get all ready, with several bands, in marching order. There was even an Esperanto banner to march under and I seem to remember a group of juveniles belonging to something called the Kiboo Kift.

The like was not to be seen, nor the atmosphere felt, until the first Aldermarston marches after the war.

There was, I need not emphasise, plenty of hard routine, continuing political work to be done as well. But you have to appreciate the atmosphere in which that work was carried out to get the feel of the times.

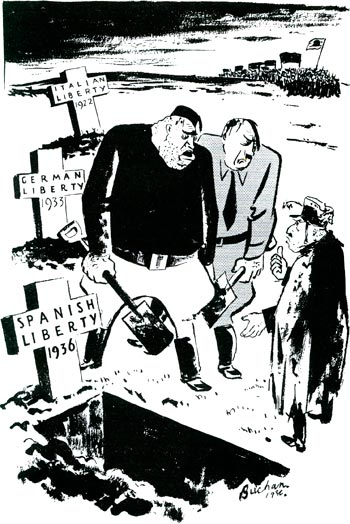

On the more personal side of Boswell’s collaboration with fellow cartoonists James Fitton and James Holland (they were widely known as ‘The Three Jameses’) added a graphic pungency to the Left Review. I have in front of me a book published by Martin Lawrence in the form of a diary for ’36 containing twenty six cartoons by them. It is a good example of their ironic comment and deceptively simple style.

In their draughtsmanship the three James were similar but different. Fitton was perhaps the more sophisticated, Holland’s style was more traditional, Boswell came between the two but recognisably his own man. His black and white cartoons were influenced by George Grosz, ferocious satirist of the German bourgeoisie and militarism after the First World War. He did not have the savagery of Grosz, no British artist did. Or should I say, he did not have the savagery then, it is a point which arises later.

In Boswell’s contributions to the book inert, raw-beef business men, civic dignitaries and Special Branch types are put down with a cold economy. At the lower lever there is ambiguity, with the same economy, of the lumpen soldier and his pregnant wife, for the soldier who is at once victim and victimiser.

These examples of his work are in the nature of social comment. In the directly political cartoon which he did for the Worker there is a posterish, didactic quality, calls for action in vein of Myakovsky’s pictorial work after the Russian Revolution, whereas Left Review drawings of establishment dummies, county characters and over-fed ladies make you shake your head and say, ‘What a bloody silly society!’ Which it was.

Attacking this bloody silly society I have a bit of political polemic of the time. It is a sixpenny booklet ‘It’s Up To Us’ published by the Left Review, consisting of a potted international history from the start of the first world war to the struggle to avert the second. Figures, statistics and diagrams are reinforced by drawings from the three James’ and others. Complete with colour it was, I think, designed by Boswell. The reason I mention it is that among the many pre-war pamphlets it was, besides being clear and effective propaganda, ahead of its time in pictorial and typographical technique. It could be said in the bourgeois sense, to be a collectors’ item, if the bourgeois collected such items.

During this time he was also producing line and colour sketches of market places, public houses and shabby streets in the hinterland of Camden Town. It was a pretty full life for one who liked normal social and family pleasures. When my wife and I visited the Boswells at their Parliament Hill flat the conversation was as likely to be about French films or gossip about politics. He introduced me to the French satirical magazine L’Assiette Au Beurre. We introduced them to our local music hall at Islington Green, Collins. But duty was never far off. In the alarums and excursions of that period sudden call outs were apt to occur. I remember marching with him down Tottenham Court Road as part of one such hastily summoned demonstration against some forgotten piece of Fascist nastiness. As we marched, we chanted:

Hitler and Mosley, what are they for? Thuggery, buggery, hunger and war!

Not quite the sort of slogan to be worth a regiment today.

One of the last meetings I attended with him was a hilarious gathering of the artists’ group. About thirty or forty were present to discuss the proposal, handed down from on high, that they should all join one appropriate trade union to demonstrate their identification with the working class. After much argument and soul searching, it emerged that the most suitable union to join was The Glass, Sign and Ticket Writers’ Union. As good, disciplined party members they accepted the decision, and as individual artists no one, as far as I know, carried it out.

In the end - no connection with the previous story - Boswell got fed up with being a good organiser. The instrument was Henry Parsons, a convivial older party member who had held various jobs in the party hierarchy. I liked Henry and he told me the story himself. Having a drink with Boswell, after a working session at King Street, Parsons in that peculiarly English jocular-insulting manner told him he was such a good organiser he ought to pack up the art lark and concentrate full time on the job everyone said he was good at - organising. ‘You know what,’ Parsons said with a great guffaw, ‘Next day he packed up all the organising jobs he had and went back to his drawing and painting.’

By this time war was imminent. When it came I lost sight of Boswell. I went into the Royal Artillery and he went to the Middle East with the Army Medical Corps, and other matters occupied us for some years. He was posted back to London before the end of the war, in ’44, I think. On leave, I met him unexpectedly in one of the war office outposts in, of all places, Eaton Square. He showed me some water colour sketches of life in the desert, drawings of petrol dumps, medical stations, ration lorries, the general routine of camp life and squaddies and wadis.

After the war (and that was six years out of our life) things were vastly different. Notwithstanding the great Labour victories, the elan had gone. Politically it was a hard slog and, in the long term, one of diminishing returns. Boswell was Editor of Lilliput magazine then. We saw each other infrequently. He was not around so much and was on the turn, I think, away from politics. Early in the fifties he went to the south coast with his family and was reportedly painting large canvasses, subjects unknown. There was no break in our friendship but it subsided, as so often happens, to Christmas card terms.

I did see him one last time, ’59 or ’60 it was. He sent me an invitation to his one man exhibition at the Drian Gallery*. I went deliberately the day after the opening which had been, as I expected, a grand reunion of his many friends who had not seen him or each other for some years. When I came the following day we went round the gallery together, undisturbed. The paintings were all large abstract, rich colour, heavy impasto, impressive in a way. He told me with the old enthusiasm what he was thinking and what he was attempting to do. ‘It’s the only way to paint, you really should try it,’ he said, always the propagandist. We had an amiable session in the pub round the corner and that was the last time I saw him.

The footnote is, of course, that I did not see the notebook drawings till the Nottingham exhibition of ’76, after his death. These allegorical drawings of militarism he did during the war but were not published till then. In the desert drawings I had previously seen there was no indication of the bitter festering feeling of these anti-military tableaux though they must have been done at the same period. The notebook drawings are technically different from his previous work. The brisk, sketchy naturalism of the water colours and the spare line of the cartoons are replaced by short, staccato pen strokes, broken and jagged, adding up to the general effect of a bad dream. Indeed, the drawings Sick Parade, Church Parade and Bullshit have a nightmare, Goyaesque quality.

Personally I do not see a dichotomy here. The water colours of Camden Town and the Middle East are the exercises of an artist practising his craft. One does not, one cannot, live in the contemplation of horror all the time. There is, in fact, a fairly natural progression from the early didactic cartoons and the Left Review social satire to the terrible disgust at the human condition of the wartime notebooks. It would seem as if, after translating the shock and the affront onto paper, he drew a line underneath, so to speak, and turned away.

Perhaps it is small wonder that his next step was paint, rich, luscious, abstract paint. For myself, when I think of Boswell, I think of his activities in all areas in the thirties and of his human commitments of that time of which the notebook drawings are a summation. As an artist he has left a body of worthwhile work, it had an impact in times past and in has an impact in time present.

James Friell (‘Gabriel’), (1912-1997), political cartoonist for the Daily Worker from 1936 until 1956, when he left after the Soviet Union invaded Hungary. He then joined the Evening Standard (1957-62), drawing as ‘Friell’, and he later drew cartoons for consumer-interest programmes on Thames TV.

* The Drian Gallery exhibition took place in 1962.