Drawing

There was James Boswell, the painter and there was James Boswell, who drew and they were different although every drawing was a potential painting. He always drew, from when he was a small boy when he surprised and delighted his parents by drawing on rolls of wallpaper. He came to London and continued to draw anything he saw which interested him. He drew in pencil, ink, conte crayon, with reed pens when he could get them, on scraps of paper, sheets of Ingres or anything he could find, trimmed to fit a small portfolio which he then used as a drawing board or in a sketch book. He was never without one and he filled many.

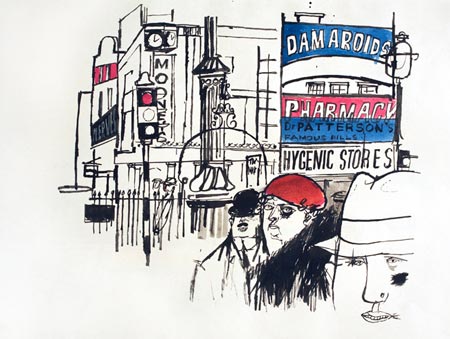

In the Thirties, when he was out and about he drew with a thin nibbed fountain pen. The drawings are accurate, detailed and free, people, streets, events, odd ideas for something which came to mind and references for something he needed to remember. Many of these drawings would be the raw material for something else, an etching, a lithograph or an enhanced version of the same drawing, wonderful, eccentric women, dubious looking men, street furniture, buses, shops, posters, mostly in Camden Town, Kentish Town, Charing Cross Road, Leicester Square. When he drew in his studio he used Indian ink and a dip pen which he padded with gumstrip to give him a better grip. Studio drawings were often bolder, perhaps with a little colour added. In 1939 he went to Paris and drew in a brothel called Le Sphinx, drawing on small sheets of paper and in a sketch book He produced further drawings when he was home, using his wife Betty as a model for several of the girls. The drawings are bigger and lovely and don’t look like they were done on site but working on anything large in such an environment would have been impossible.

The war changed everything. From 1940, he became a reporter and filled his sketch books with soldiers and dirt and dust and information as well as savage commentaries on war, bureaucracy, the stupidity of it all and the appalling indifference of career officers and clerics for whom he developed a considerable dislike. Boswell discovered during the war how to turn his skills as an artist into graphic reportage and the work is remarkable and unique. He could draw what he wanted because he was doing it for himself and wasn’t obliged to produce positive images of war to satisfy a committee. When he returned home he re-worked many of the drawings from his sketch books on paper which was more substantial and to which he added colour, succeeding in losing nothing of the lively originals.

After the war he kept on drawing, anywhere. On holiday he would sit on a beach or on a terrace, cooking in the sun and drawing what he saw. He drew people on a trip to Romania, old houses on a journey to Australia and New Zealand. In London he drew the streets and the small shops. The drawings continued to be detailed, elegant, informative. His fountain pen got bigger, the nib got fatter and the drawings got bolder but he never stopped drawing, always in ink or pencil. Even his tiny pocket diaries are written in ink. In the fifties he often worked with a thick Black Prince pencil, powerful drawings occasionally partially coloured with Derwent coloured pencils.

In 1952 when the opportunity presented itself to go back to basics, he hired models and drew nudes, usually freely with ink or brush but often in pencil. He could do a lot with one single, elegant line. At the same time he was drawing cityscapes, seascapes, Brighton, Shoreham beach. He made several beautiful drawings on holiday on the Ile de Re in 1953. Sometimes a commission for a book would result in drawings instead of illustrations – there’s a subtle difference.

In 1967 he went to the Isle of Wight, was captivated by the reed beds which supplied him with enough reed pens to keep him going for ever. He used them to make many drawings of the reflections in the harbour. Later, in Venice, the lagoon and Torcello filled sheets of paper with exquisite, simple, elegant lines, some little more than a shimmer on the water, some detailed images of much loved buildings.

His legacy is glorious.

Sal Shuel